On Father’s Day weekend, my husband and son took a trip out to see some family, planning on staying overnight so they could attend a Sunday baseball game. I went out to the car to say goodbye to Liam and as I pulled away from his sticky preschool boy hug, he said

Mommy, please come!

For many mothers, this is a standard, heartwarming child’s plea: “Mommy,” our children urge, “don’t go!”

Another example: At Liam’s end of school year party, he refused to participate in his class’s end of year show. Once he sees Mommy, he breaks down completely. He’s always the group’s only child unable to join in when Mommy’s around, needing me instead of his friends. This is a habit formed since he was two years old.

For adoptees-turned-mothers, these events are harsh skips in our daily soundtrack, forcing us not into the quiet reverie of motherhood but into that complicated place called abandonment. What, I wonder, have I done to reveal my life’s secret anxiety?

I consider all of this in context of not just my own personal history, but the history of the many adoptees who become parents. Is our heightened sense of loss, our prescient understanding that at some point our children will grow into adults who may or may not reflect our parental failings, so tightly wound into our interactions that we pass it on to our children?

I can’t speak for others, but to me, it’s a fascinatingly painful fear. My son’s innocent pleadings for a Mommy he never realizes could leave both confound me and, somewhat embarrasingly, generate a deep sense of envy toward my own son. Because of my simple decision to not give up on him, I’ve constructed for him a foundation unshakeable–unless, of course, I walk away.

Seeing its utter simplicity, seeing just how easy it could have been for my life to not be marred by adoption’s persistent complications, repulses me. I know for a birth mother, adoption isn’t easy.

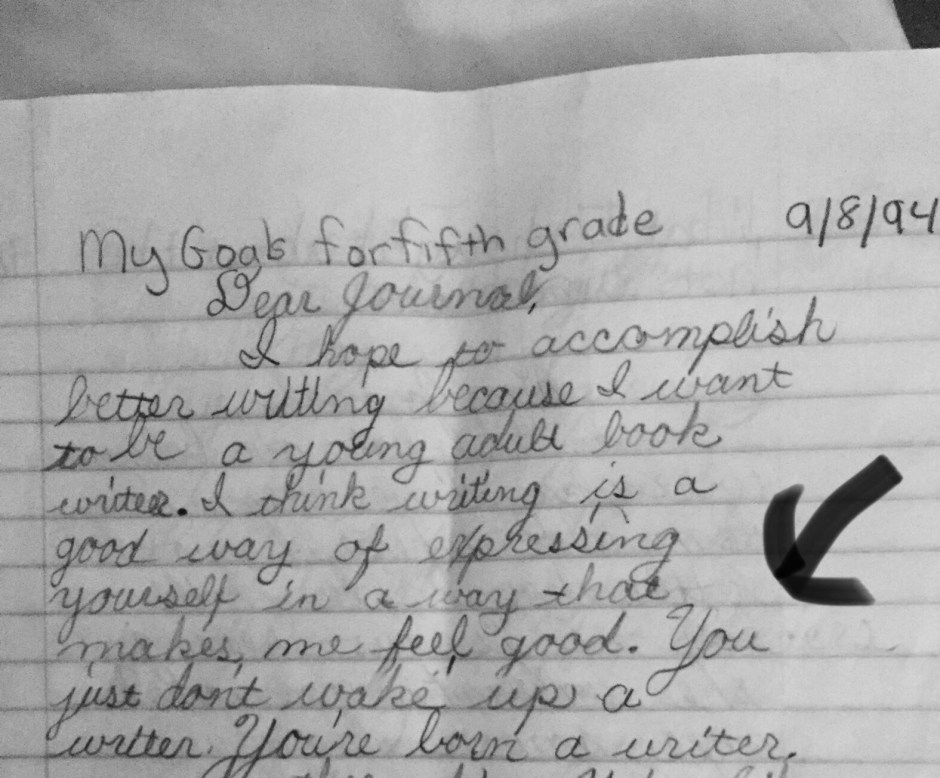

Still, when I consider this notion of presence equaling simplicity, my memories rewind themselves like a tape playing backwards. School plays and insults and Christmases and harsh words and smiles become garbled together in frenzied reversal. As I begin with my birth–the only thing my son and I have in common is that we were born–I start my life over, trying to replace my son’s experience with my own. Eventually I give up, unable to write a story that never existed.

At that point, I wonder: Is being a “a good mother” one who merely sticks around? Does that mean I get a pass to be as mediocre or terrible as possible, simply because I know that no matter what, a child almost always wants nothing but his birth parents–regardless of skill?

Obviously, parenting takes far more effort than just described. As an adoptee, however, the innocence of motherhood–the innocence allowing moms to make mistakes and forgive ourselves–was taken from us when we ourselves were taken away.

Like other parents, we know how carefully children watch their parents. But unlike the unadopted, we have a full appreciation of the long-reaching impact our presence has on a child. Adoption ends the childhood innocence of believing our parents will never stop wanting us. It destroys the myth of family as safe haven. Adoptees, unfortunately, know how untrue that can be, how carefully we tread the line between good and bad parents. Despite it not being an easy choice to walk away (I wouldn’t–ever), I don’t think we can ever fully believe that, since it happened to us.

Because of adoption, the joy of motherhood–one I’m owed–has been destroyed.

As Liam grows older, articulating his desire for Mommy’s closeness is becoming stronger and more frequent. With his developing sense of self and familial bond–that of which I still struggle to experience–he unintentionally and continuously highlights a permanent space between us. I actively work on closing it while remaining aware of our life’s distinct path, a path chosen not by either of us but by those who swore to love us forever.

People who don’t believe in adoption trauma didn’t see my three-and-a-half year old’s son reaction when I angrily told him

People who don’t believe in adoption trauma didn’t see my three-and-a-half year old’s son reaction when I angrily told him