Here’s another post where I’m hashing out a concept I just read about, so if I got it wrong or you have something to add, please share!

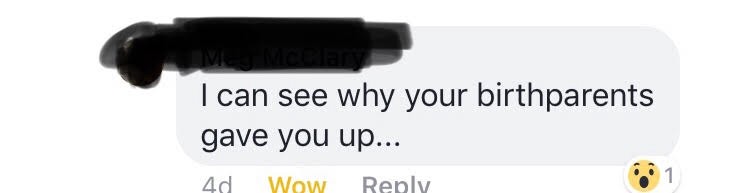

Love is a tricky term in transracial adoption. Many adoptees feel that love, in its most commonly understood form, is used as a way to silence our own interpretations of our experiences, with love being the trump card pulled when we express viewpoints opposite of the dominant one: “But your parents loved you like their own and loved you enough to take you in!” or, “Your biological mother loved you so much she gave you up.” Because of the nearly impenetrable love-dominant messaging inherent in adoption, adoptees feel compelled to stay silent or risk serious conflict and emotional upheaval if they try to push conversations past and through love.

Most parents, adoptive or not, love their children. But love in adoption carries more weight and risks than traditional parent-child relationships. Adoption’s love, in its rawest form, is transactional. It is based on a parent’s obtaining of a child and learning to love someone based on a promise to care and protect. In exchange, a child receives a home, an education, and other material and immaterial things that presumably offer a more productive life than the imagined alternative. This is not to say that this kind of love can’t be learned or genuine or is “bad,” but instead I’m showing that adoption almost always carries with it the premise of love, both received and given.

The growing scholarship and public conversation on transracial adoption, however, is showing that love is simply not enough. Love in adoption seems, to me, predicated on creating a family structure similar to one not made by adoption and one based on same-race (or even interracial) biological kinship. Love, at times, is weaponized against adoptees. It often forces adoptees into identities and narratives that might not reflect their own self-conceptualizations, and that’s when love becomes a powerful, dangerous tool, and where it conveys ownership of a body and a narrative.

What is Radical Love?

An alternative form of love that may better serve transracial adoption as a system and as a family structure might be radical love. What makes it radical? Well, like all things stemming from academia, it’s a term that takes two already loosely-defined words and combines them to make them confusing and higher-browed than they need be (sorry, academia). There’s nothing “radical” about it (like, you don’t need to go running through the streets with a sign or drastically change your worldviews; it’s also not “radical” in the 80s sense of the word, either–sorry again) and the “love” it promotes goes beyond thinking about how we care about someone. It’s also not explicitly about romantic love, either. Instead, radical love offers us a new way of being with and being for not just ourselves, but the community (and family) surrounding us.

Because radical love has no official definition, I will borrow from Claudia Cervantes-Soon’s interpretation:

[Radical love] is “manifested through mutual humanization, the transgression of borders of power relations and gendered expectations, and a commitment to the collective struggle for justice.”

In other words, it’s about framing the way we love one another in a way that respects and overcomes each other’s position in society, where you recognize that that person’s perspective and identity is deeply shaped and entwined with the internal and external relationships and systems they encounter. We radically love someone when we recognize that our power can impact another negatively, and we radically love someone when we learn to listen to their stories as part of a social whole that validates and empowers, rather than subordinates and controls.

For me, the appeal of radical love is its emphasis on community and its de-emphasis on the individual. Love is not a one-way avenue, nor is it a two-way street, and it is especially not a dead-end! But to me, radical love embodies respect and listening, where your needs and perspectives aren’t set aside to account for another’s, but instead interacts with the other person’s, and ultimately, the entire community and society.

Radical Love and Transracial Adoption

So, how can we apply radical love to transracial adoption?

First, we promote transracial adoption as a person in power (the adult; the white adult) entering into a legal form of kinship where transaction is implied. Rather than seeing that fact as a cold, unloving part of family-building, we accept it. We accept the challenges that form of kinship can create, and we can recognize the power imbalances that might happen throughout the family’s life due to this inherent structure.

Second, we recognize that our family isn’t formed in a vacuum. Each member–children included, non-White children especially–occupy a lower social space in the family (parents above children, older siblings above younger, etc.) as well as in the community as a whole. We embrace and show our love by engaging in conversations and activities that show we are actively addressing their oppression, in ways that go beyond treating children as “passive objects” (thanks again, Claudia Cervantes-Soon!) who simply absorb social messages and instead as active participants who have the agency to create their own identities both inside and outside of the family.

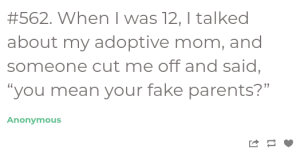

Third, and most importantly, we promote the development of unique identities in the child, while respecting that these identities are fluid and will shift in reaction to family events as well as their perceived social status. These identities must go beyond the child being “adopted” or not. The child may reject their adopted status for a time, or forever. The child may wish to identify closer with their racial and biological roots. Or, they might not. Regardless of the child’s comfort or discomfort with what adoptive parents have provided out of love, a more “authentic” form of caring would be one that proactively engages with a child’s rejection of an imposed identity (that is, an “adopted child”) and instead of pleading with or scolding them into changing it, a parent demonstrates “unconditional acceptance”–the same form of respect that they would wish for themselves.

The idea of radical love isn’t to simply sit back and let a child run amok. It also isn’t blindly saying “yes” to a child without any dialogue or feedback. Instead, it’s a conversational way of allowing for a child to claim ownership of their identity, despite the traditional adoption narrative that implies they are “perpetual children” who exist because of an adult’s love.

Adoption agencies should consider radical love as a progressive acknowledgment that the children they serve (because it’s supposed to be “for the children,” right??) do occupy subordinate societal positions, and the children of color are absolutely denied the same privileges as White children. Radical love is more than performative educational programs designed to inform White parents about their child’s racialized experience; instead, radical love would center the child’s identity–and arguably, their entire sense of self–as a growing, evolving, fluid construction of their own design, that they themselves own. Radical love frees the child from its beginnings as a “needy” object in need of a home. Radical love, by contrast, incorporates their experience as a person taken in by adults and allows them the power to move in and out of that status as the child desires.

Radical love, in essence, could transform transracial adoption by opening up the boundaries of family and situating it within the greater society–just like any other family. Even though arguments historically position families as a private space, the truth is that families–especially transracial adoptive families, because of their obvious visibility–are indeed a public entity that is influenced by the state and community in which it resides. Radical love could also destigmatize adoption and adopted children, by giving adoptees the space to question and push back on the oppressive design of adoption (most notably, legal documentation issues come to mind), while allowing them to interact with their families and friends in a way that no longer others them as someone taken in, but instead repositions them as someone taking control.